I’d meant to write about spinning and swimming, instead I’ve been preoccupied with thoughts of damage, mending and repair. I hope you’ll all appreciate how that shift - given the times in which we live - came into being.

I’ve been trying to establish if mending and repair are one and the same. I’m also growing to appreciate both as travelling far beyond material boundaries, to see that mending and repair might relate to situations, communities, relationships. Most of my artistic practice occupies this space, place really, because there is something so considered, slow and still in my mending and repair (I’m holding onto both, for now) that the two of us, me and my subject – maybe a sweater, sock or knitted toy – transform space or non-place into place.[1]

That’s the first step in drawing out the differences between repair and mending, ease of mobility and my capacity to transform non-place, or transitional space, into place. My work requires only my hands, needle, thread or yarn and perhaps the occasional safety pin. It is transportable; I can work at the kitchen table, in the studio or on the train. My mending can be bundled together, squirrelled into a bag, and squirrelling feels right. Public mending still feels transgressive to me.

When I take my seat on the train, unwrap my bundle at the drop-down table and take up needle and thread, I make for myself a heterotopia of care. Perhaps not quite the heterotopia imagined by Foucault,[2] but a very particular world within a world. I think of this world as a bubble; insulated, protective and reflective. A bubble that is more than the familiar flow state described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a state of being that comes through and out of a skilled and familiar practice and describes an absorption that modifies time and place, such that we might swim twenty lengths without knowing, or reach the end of knitting a sleeve without remembering the beginning; ‘she’s lost in her own world’. For me, my particular bubble is an extended moment of material investment that connects me with the object of repair and beyond that, its subject, the owner. This soft object operates as a conduit. This can happen whether or not we are known to each other.

Margot Waddell uses the term ‘kept in mind’ to describe thinking of someone in their absence.[3] This absence as presence thinking occurs particularly when I’m repairing well-worn garments, as if the garment has the capacity to collapse distance. Keeping someone in mind, particularly when the thinking is accompanied by gestures of care – like cooking a meal, running a bath, making a fresh bed in anticipation of a loved one’s return – has therapeutic consequences, and not just for the recipient. I speak from this place. I know it is possible to find tenderness in mending a well-loved sweater, to think lovingly of another’s flesh and well-being, to find my thoughts travelling backwards and forwards, as surely as weft follows warp. I know it is possible to be restored by mending. Mending is an act of self-soothing. We all need such bubbles.

An on-line image search for articles on mending and repair shows mending as pins, needles and threads. Repair is a well-resourced tool box, possibly a toaster or washing machine. Repair means metal boxes, circuit boards, fuse boxes, heavy stuff. A thought; try fixing your toaster on the train. Conversely, I doubt I’d find any ‘kept in mind’ tenderness in repairing a washing machine. There’s something very particular in repair, no room for ‘make do’ in fixing a toaster. This may cause uproar, but mending – at least how I perform it – need not be perfect, by which I probably mean invisible. Mending returns a thing to function, mostly.

Like my friend Bridget Harvey, I have always been a mender. But while Bridget describes her formative mending years as relying heavily on superglue, mine – being somewhat ahead of Bridget’s – are less new-fangled, having a greater affinity with the close at hand. I have vivid memories of skirt and trouser hems secured with Sellotape and staples, and my English teacher horrified by the scarlet blob of nail polish marking the end of a ladder in my tights, the shame! The same teacher who once sat with her sixth formers sporting a string vest over bare flesh.

My mending has refined over time, but it is still possible to measure my progress in the objects I have held onto – and mended – the longest. Ones that belong to me. The dynamic repair of my fifteen-year-old Corgi cashmere bed socks, for instance. As a fledgling knitting mender, I used the same technique, darn weaving, to strengthen worn thin areas as I did for the holes caused by moth appetite. Now wiser, I understand the value of a pre-emptive repair, that duplicate darning – sometimes called Swiss darning – where needle and thread trace the path of knitted yarn in a side by side, face to face, companionship.

My much loved and much mended Corgi Cashmere Socks

Bruno Latour reminds us that ‘things do not exist without being full of people’[4] and this is particularly true of clothing, most especially those I mend, always so full of stories. One reason I write is to better understand my own practice, in this case, whether I should describe this part of my textile work as mending or repair. I think Celia Pym, mender extraordinaire, speaks to Latour when she writes that ‘Mending is an action specific to cloth and the body’ and I think too that I have found my place.

I saw Threads in its last few days at the Arnolfini in Bristol.

It was especially pleasing to see Celia’s work, particularly the Hope Sweater 1951, a child size visibly repaired fair isle sweater that first belonged to Celia’s mum and then her brother, William. In the years of storage that followed it became a feast for moths. Celia has worked a tender landscape of heather yarn out of this very considerable damage. There are large areas of replacement knit, particularly the chest area, where childhood food spills make moth damage more likely, and areas of weave darning to the insides of both cuffs (I initially wrote wrists, again that slip between clothing and body). To see the sweater clearly, two things are required, to crouch down – because it is displayed at the height of a small child – and to obscure the glare of the gallery’s intrusive spotlighting. Both habits, bending and leaning in, are felt at the body and this is significant.

I remember how I’d entered this space, I was pricked, in a proper Barthesian manner,[5] at seeing the sweater so low at the wall. In fact, I recall bringing the flat palm of my left hand to that point where the neck meets the chest, my sternum, and expelling a breath as if for a chest examination. Hope’s Sweater was the first thing I walked up to, slinging my bag to my back, crouching down and leaning in, stooping as if to greet a child. Twice moved, physically and emotionally. And there I stayed, and might have stayed longer, if I’d not become concerned at how odd I looked.

I used landscape earlier, and to this I return. Celia’s very particular care, or perhaps tending is more appropriate, has the effect of constructing a new surface whilst simultaneously reshaping the old. My eyes, already tuned to close up textile looking, scan this renewed landscape. Heather coloured yarn, spreading like moss, resonates with the sweater’s origin, Shetland. Celia’s carefully reconsidered reknitting of the shoulder ribbing, knit one purl one, melts me. The margins where heather meets the original body, where Celia sets anchor, always important in darning since both – old and new – must blend for a secure mend. How the weave repairs at the cuff, more densely packed than those at the main body, have the effect of lengthening the arms and altering their posture, so that I imagine hands turned outwards, towards me. Celia tells us how she tried to ‘hold onto’ the ‘tiny red fragment’[6] at the centre of the large darned area, and I think I have caught this in the first image. That tiny red fragment, fibres like candy floss, appears to wrest free of Celia’s grasp, a fugitive island.

Celia Pym Hope’s Sweater, 1951, moth damaged sweater and darning, 30 x 40 x 3cm, 2011 (my images)

In all this, it’s easy to understand how mending and the body are so related. With recent events in mind, my revisiting of this beautifully tender repair of an accidentally damaged body of cloth is deeply affective.

On the train home I remembered Olivia Laing’s appeal for art ‘art that repairs, art that longs for connection, or that finds a way to make it possible.’[7] Celia Pym’s work is of this place.

Laing writes of Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (for David) of the peeled and torn fruit skins, dried and ‘sutured back together with red, white and yellow thread, embellished with zippers, buttons, sinew, stickers, plastic, wire and fabric.’[8] Strange Fruit is a compelling act of repair, packed full of tenderness. But it is also, perhaps unintentionally, playful. It reminds me of Pym’s paper bag repairs and – in its use of the close at hand – even more of Harvey’s ceramic repairs. I saw Bouke de Vries’s A Rake’s Progress at the John Soane Museum on Bridget’s recommendation. It was good, a narrative work following close to the tale and beautifully displayed, but not as good, for me, as Bridget’s work. Perhaps this has something to do with the artifice surrounding work that is deliberately broken for repair, or made as if broken. I’m learning to hold back, there’ll be more of Bridget’s beautifully ludic work next time.

Bridget Harvey Paper Tape Plate (2015) broken blue saucer, brown paper tape. (shared with permission)

This month I watched Fashion Reimagined and The Nettle Dress.

Both films are concerned with mending and repair. The first, the environmental damage caused by the fashion industry. The second is more specific, both are documentary.

The Nettle Dress exists as a material manifestation of psychic repair, of the work we must each do to restore or mend ourselves after loss. We follow Allan Brown as he spins, weaves and fashions a dress from nettles. It is gentle, studied and packed with physical and emotional labour. We are witnesses to something Freud called the work of mourning.[9]

It is a beautifully poetic film with a proper storytelling quality, enhanced by the chapter headings and the lovely thing that happens when you work so closely to process a raw material; a beginning, a middle and an end. Allan talks of learning the right way ‘to grasp the nettle’, a good metaphor for this first and perhaps hardest step in his journey. And there’s little hesitation in that grasping; he leans right in, a proper immersion, a giving in, or giving over. I can’t escape the thought that work like this involves taming, of the nettles’ transformation from nature – harsh, stinging, resisting intervention – into culture and yet still retains some of those original suit of armour qualities, ‘I’d wear nettle into battle.’

We watch the gathering, the retting, the daylight spinning, and candle light weaving, Allan’s seemingly endless labour. I thought he might be lost to both his grief and the process, but grow to think he is/was neither. Instead, his leaning in becomes his journeying map, ‘I’ve just got to follow the next step, do the next thing’. In his making - his transformation - Allan fabricates a companion for his own emotional journey. The final warp thread is cut - the cloth freed of the loom that held it in place and afforded its making - a weight drops to the floor, not quite a full stop. And here I am so tempted to reach back to mythology, to Theseus, Ariadne and Patient Penelope. But I’ll hold back, patience (it’s not always a good thing to reread just before publication deadline!)

The Nettle Dress can shift towards such intensity that I sometimes felt guilty of intrusion. I’m reminded of CS Lewis’s A Grief Observed, another moving autobiography of love and loss, of grieving. In my film watching notes I wrote, ‘This is a narrative object, an evocative object.’ Sherry Turkle describes an evocative object as ‘a marker of relationship and emotional connection.’[10] This nettle dress is one such object. Allan reminds us of his intimate relationship with the dress, how its making is marked by their mutual adaptation, their simultaneous making/remaking, ‘I was transformed by the nettle.’

I’ve decided to share thoughts on Fashion Reimagined another time. Too much already and I’d like to discuss reading that fits here.

It's not unusual for me to read two books simultaneously.

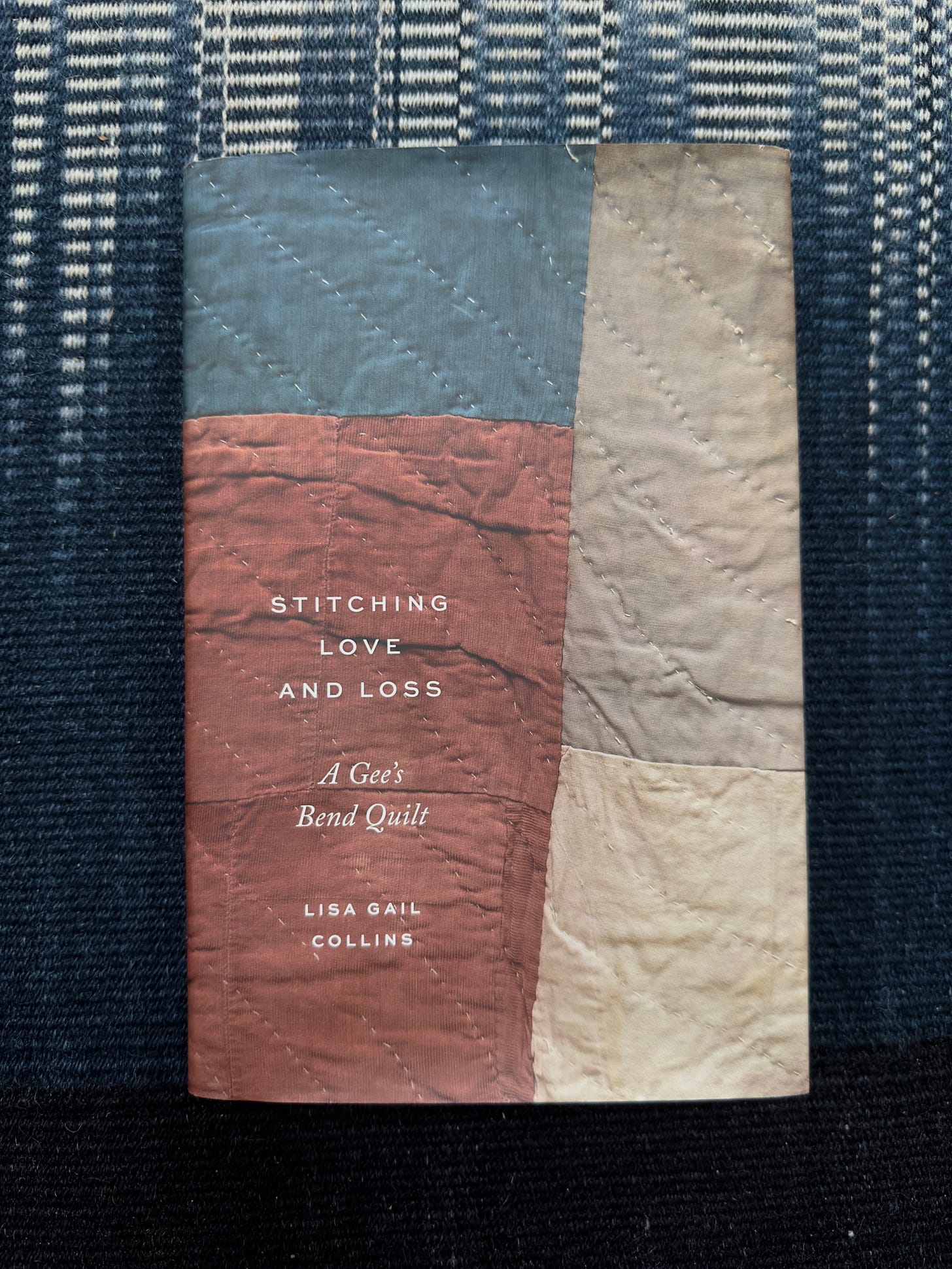

Currently, Charlie Porter’s Bring No Clothes and Lisa Gail Collins’s Stitching Love and Loss: A Gee’s Bend Quilt. Both are stories of our relationship with cloth and the body, the latter sharing similar themes of making and psychic repair as The Nettle Dress and yet richer for being both biography and social history. I’m less than half way through each and yet already know them to be richly sustaining. Porter’s book is more of a page turner, a kind of romp through the Bloomsbury set. I’m far enough in to read Porter’s moving account of learning to use a sewing machine and remodel a favourite t-shirt three days after his beloved mother’s death, ‘I was grieving through making’. Charlie’s story is not so far from Allan’s. How does it happen that I was almost there – finished with this writing – and took a bath with Charlie Porter to read this? The very best sort of serendipity. So much connection, a proper rekindling of love for my subject, making and writing about making. And now I’m stuck with knowing I’ll finish it soon and simultaneously needing a book to accompany me on three weeks of travel. How will I leave it for someone else once that last page is turned?

Love and Loss requires and deserves much more from me. Because I most often read in the bath or before sleeping, I don’t easily remember what I’ve read and this is a book so rich in knowledge and emotion, so densely packed. The Porter has more space around it, but I’m sure this feeling is born of familiarity. Love and Loss is different; it needs my daylight hours. I share the quilts of Gee’s Bend in my teaching. I’ve watched films where the women talk of their work, read books written by others, but have yet to find anything that brings together testimony, social history and quilt making as successfully as this. Missouri Pettway makes a quilt from the workwear of her husband Nathaniel, who died at the age of 43. You can see the quilt on the front page of the book, but also at Soul’s Grown Deep. Anyone living with or making quilts should read this, the historical context - how Gee’s Bend came into being - is essential reading.

I feel I have written so much and yet touched all so lightly. Perhaps I ought to ply this lot together, bring the many strands into one? I have a large sheet of paper on my desk, it sits under my keyboard. It’s not blotting paper, more an aide memoire I use when teaching, chatting with friends and reading through texts. There have many such sheets. The current one, here for the making of this chapter, bears the declarations ‘Mending is for soft things, those things close to the body’ and ‘making helps us mend ourselves’. That feels right and I hope it’s enough, because I’m not going to sew this up, let’s leave a way in for next time.

Some final bits…

Winter Gathering

My Quilt Gang, there must be around 80 of you, are invited to a winter gathering on line. A chance for me to see you and for you to learn a new skill, working with curves. Everyone will get an email detailing tools and materials in the next few days.

January Quilt with Me

The January /February dates are January 18th and 25th, February 1st and 8th, with a quilt share on February 22nd. Thursday evenings, 18.30-20.30hrs (UK). The full cost is £130. This four week course takes you from piecing through to binding a quilt. They fill quickly, I’ve not released dates on instagram yet and some places are reserved for those who missed out last time. I’ll post on instagram at the end of November. Message me on Instagram if you’d like a place.

Summer Atelier in South West France

Shared with Chloe Briggs aka Drawing is Free. This is a week-long drawing and textile retreat ‘Conversations between Drawing and Thread’ with the two of us at Clos Mirabel, which is gorgeous. This is a proper treat. I’m travelling by ferry and car and will bring lots of samples, materials and textile books. Please contact Clos Mirabel to book a place, or me or Chloe for more information. Small group with limited places.

Finally

I want to keep The Cloth Botherer accessible. I’m interested in building a community and would like everyone to read it. This means I don’t have any plans to put my writing behind a pay wall and don’t have levels of access. But I recognise I need encouragement and support, who doesn’t? If you have enjoyed reading this, and can afford to pay, please do consider buying me a coffee - just click the green button - and thank you to everyone who did last time. The coffees and feedback are very affirming, they fuel my desire. Thank you, Angela

Notes

[1] There are many excellent books exploring our relationship with space and place, this one, by the French Anthropologist Marc Augé ‘Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (1995) is a little old. I used it to explore ideas of space, place and transitional space with students. Augé saw non-place or transitional space as characterised by movement and lacking permanent association, such spaces might include airports, motorways, service stations and, usefully for me, rail travel. In contrast, place is characterised by connection; it is occupied, organic and relational.

[2] Michel Foucault described heterotopia as discursive spaces within spaces that are somehow disruptive, disturbing, even transforming. I have been creative with his thinking and appropriated his idea to claim public acts of mending, those typically of another world - the domestic interior - as heterotopia. It’s a bit fanciful of me, but just imagine the transformative energy of a world full of mending heterotopia.

[3] Waddell, M. (2002). Inside Lives: Psychoanalysis and the Growth of Personality. The Tavistock Clinic Series. (London: Karnac). p.38

[4]Latour, B. (2000). ‘The Berlin Key or How to do Words with Things’. In Graves-Brown, P.M. Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture (London and New York: Routledge), pp.10-21.

[5] Roland Barthes uses the terms studium and punctum in relation to the photograph in Camera Lucida (1980). The punctum describes a moment or thing that is affecting. ‘A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).’ (1980: 27) The studium is more generalised and describes overall appeal, ‘it is of the order of liking, not of loving’ (Ibid).

[6] Celia’s book ‘On Mending: Stories of Damage and Repair’ is available from Quickthorn Books

[7] Laing, L . (2016) The Lonely City: Adventures in Being Alone (Edinburgh: Canongate) p256

[8] Ibid. p257

[9] Freud, S. (1917). ‘Mourning and Melancholia’. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Volume14, 1914-1916, (London: Hogarth Press), pp.237–58.

[10] Turkle, S. (2011). Evocative Objects (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

I enjoyed the difference between mending and repair, and wondered what it was my grandfather did in garage as he mended china plates and teapot lids. I think that was mending and not repair. Is repair putting something back together into working order as it should be and mending doing ones best, as you say to make it serviceable again?